This post provides a deeper look into the ideas of Clarity and Learner Agency, two of JumpRope’s Core Values.

WHY is self-assessment important for student growth?

We don’t have to look far in John Hattie’s list of 150 influences on achievement to find student self-assessment. It’s right at the top. Number one. In a system where the average effect size (ES) for one academic year is 0.40, Hattie reports that the ES for what he calls, “self-reported grades” is 1.44. He notes it’s not the accurate reflection of their performance that matters for student achievement, but that students have the opportunity to “predict their performance.” We do this by “making success criteria transparent, having high, but appropriate, expectations, and providing feedback at the appropriate levels” (Hattie 2012, p. 60). Hattie goes on to indicate that a crucial lever for self-assessment is the teacher feedback students receive. Hattie’s research is supported by the research of Heidi Andrade who defines the objects of self-assessment as “one’s abilities, processes, and products” (2019). Andrade’s literature review concludes that at the summative stage of learning self-assessment is unreliable largely because students typically rate their performance higher than teachers, even in cases where the self-assessment has no bearing on the final grade. Her determination for the value of self-assessment at the formative level, however, is quite different. With respect to formative assessment, across the 25 studies and two meta-analyses she reviewed, Andrade found a positive association between self-assessment and achievement (2019).

It’s not the accurate reflection of their performance that matters for student achievement, but that students have the opportunity to “predict their performance.”

Hattie also indicates that students who are classified as minorities and low-achieving, those whose low confidence and learned helplessness have been reinforced by the very systems that purport to uplift them, see lower gains with self-assessment than do their peers (Hattie 2012, p. 60). Indeed, students who have a history of being unsuccessful in school see their intelligence as static or fixed. Rather than reinforcing this fixed mindset, it is the teacher’s duty to help those students develop a growth mindset (Dweck 2006). Dweck goes on to clarify and emphasize, “the growth mindset was intended to help close achievement gaps, not hide them. It is about telling the truth about a student’s current achievement and then, together, doing something about it, helping him or her become smarter” (2015). When we effectively coach students to self-assess, we help them become smarter.

HOW do we implement effective student self-assessment in our classrooms?

According to Chappuis, there are four prerequisites for successful student self-assessment. I have suggested a previous blog post which speaks to each of these prerequisites.

1. Make sure the assignments and assessments align with the learning targets. See earlier post on validity.

2. Make sure the students know which target(s) correspond to each assessment. See earlier post on transparency in assessment.

3. Make sure students are clear on what success looks like and how it will be measured. See earlier post on “the why” and “how to” of rubrics.

4. Make sure students know what academic progress looks like. Hattie refers to this as success criteria. Readers who use JumpRope have heard us refer to it as scoring criteria. In any case, simply completing assignments is not the same as academic progress nor does it position a student to reflect on growth (Chappuis, 2020, p.365).

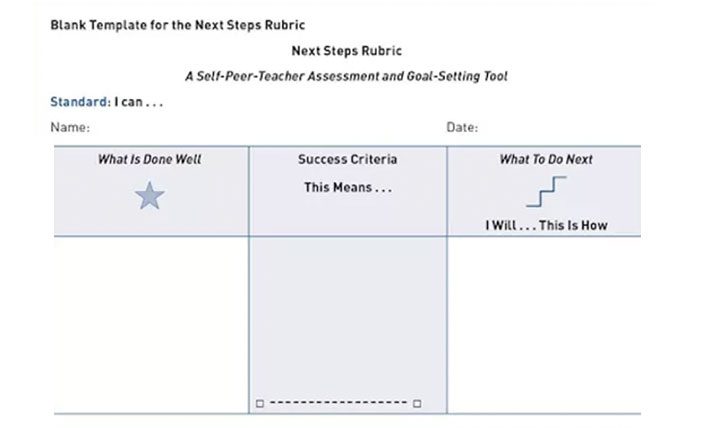

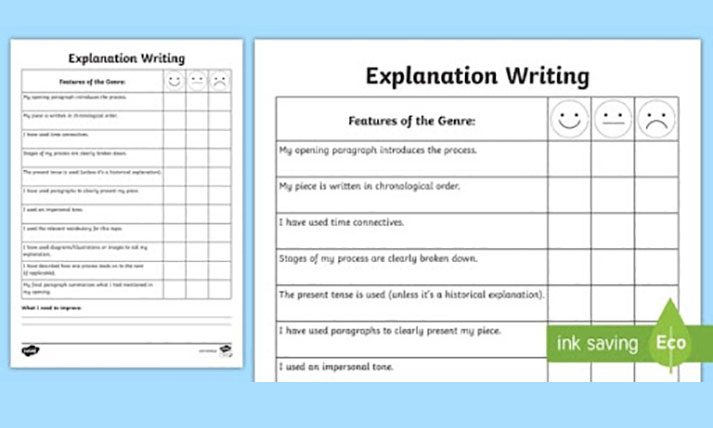

The first two in this list are the easier ones to take care of. They are largely a function of clearly framing what we will teach and assess and being transparent with our students about those things. This is not to say these things are a cinch, but rather to indicate that they rely on the tools we create and our facility to effectively share those tools. The third and fourth steps rely on the nuance within our instruction and our abilities to help students truly see the end goals and steps toward reaching them. Our mindful and careful coaching through targeted feedback helps students know what academic progress looks like and how to make strides toward it. There are various reasons for and ways to give feedback as I discuss in an earlier post. When the goal of the feedback is to support student self-reflection, I like to use some sort of form or template to guide students. In the early stages of using such a template, I might employ an “I do, we do, you do” model to help students understand the thinking they should devote to reflection and to help them frame the ways they talk about their own learning processes. I find it useful for students to return to a limited number of templates to support this process so they can engage most deeply with the process rather than continually trying to learn how to use a new tool. Below I have provided three examples of student self-reflection forms. As you might guess, this is just a tiny sample of what’s available online.

When we successfully support all our learners in developing the skills they need to carefully examine their own learning and the products they’ve created, we teach them to see their strengths, be self-critical, and see pathways to getting better.

https://sk.sagepub.com/books/teaching-strategies-that-create-assessment-literate-learners/i836.xml

https://www.twinkl.com/resource/roi2-e-2687-explanation-writing-student-self-assessment-sheet

The research shows that student self-assessment might be the most powerful tool we have to improve student learning. When we successfully support all our learners in developing the skills they need to carefully examine their own learning and the products they’ve created, we teach them to see their strengths, be self-critical, and see pathways to getting better. We empower them when we ask them to take charge of their learning and we invite them into partnering with us as we work together to help them reach their highest potential.