This post provides a deeper look into the ideas of Equity of Opportunity, one of JumpRope’s Core Values.

It can be challenging to plan for large groups of students and also consider the needs of each student. I’ve come to see that one of the most valuable tools I have to meet each student where she is, is providing individual feedback. More and more, I build time into my teaching sequences to give feedback. I plan intentionally for when and how I will offer feedback, knowing that offering it is time- and energy-consuming. As a K-12 student, my own process of learning did not include getting feedback from teachers. I saw brief, unspecific comments at the tops of quizzes, papers, and projects. Even if those comments had been specific and constructive in some way, the learning was over. I would not be able to capitalize on what my teacher had offered. It wasn’t until I started examining feedback as a variable crucial to learning that I realized the importance of intentionally building it into my classroom practice. I now see that if we understand when, why, and how to use it, employing feedback as a dedicated instructional tool gives us the chance to plan effectively for the whole group and for individual learners.

The foundation for using feedback well is establishing and building on trusting relationships and an environment where making mistakes really is okay.

Like so many other meaningful classroom practices, the foundation for using feedback well is establishing and building on trusting relationships and an environment where making mistakes really is okay. It’s no secret that the people who have the greatest influence on us are those we trust. When our students see us as partners in learning — the ones who celebrate with them as they find success and build confidence — they begin to feel at ease with us. When we learn more about them as people — take interest in their lives beyond their worksheets, science journals, research notebooks, and essays — we honor them as whole human beings. It’s the establishment of this connection which allows us to offer the crucial critical feedback they need to grow. Sure, we can skip the relationship building and still offer the feedback, but if we take the time to create these bonds, our students stand a better chance of taking our feedback.

If we think of ourselves as the architects of student learning and recognize that building trusting relationships is foundational to that learning, we can also see that the materials we use to build from that foundation are crucial. Of the 150 influences on achievement John Hattie notes in Visible Learning for Teachers, feedback ranks tenth with an effect size of 0.75. As a reminder, Hattie found that an effect size of 0.4 is the hinge point wherein the practice has a greater than average impact. Considering when and how we will offer feedback as we plan our instruction, helps us deepen learning for our students collectively, but moreover, it positions us to engage with students individually. But all feedback, as examined through the work of assessment gurus including Jan Chappuis, Susan Brookhart, and Grant Wiggins, is not created equal. There are five elements that ground effective feedback and can therefore inform our planning and instructional practices. Feedback should:

-

- be anchored to the intended learning, or, the learning targets

- happen during the learning process, while there is time to act on it

- include the expectation that it will be acted on

- celebrate strengths

- offer concrete, specific, understandable and usable steps for improvement

- lead learners to do the thinking as opposed to doing it for them

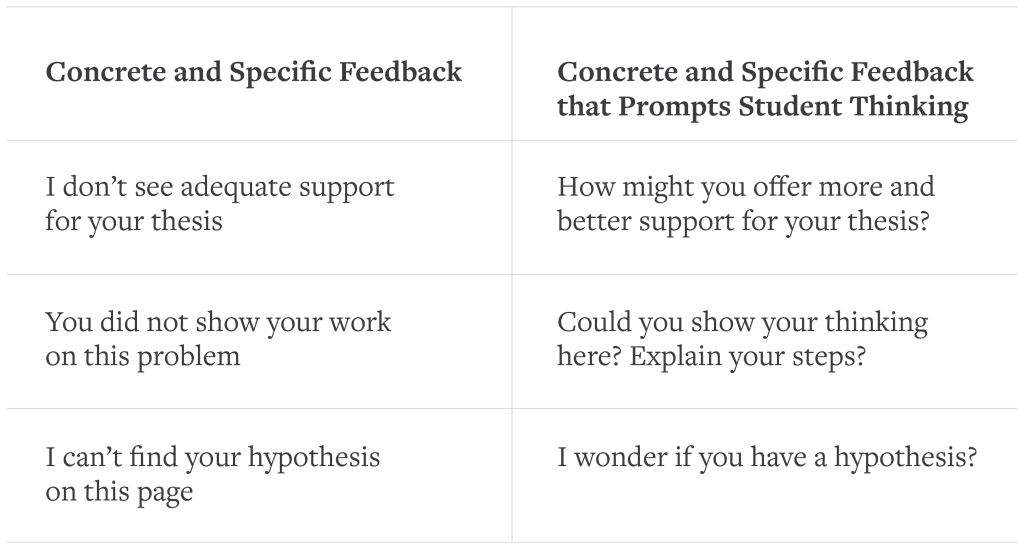

Feedback predicated directly on our stated learning goals helps students see exactly how they are progressing toward those goals. Offered with strategic prompts and questions, that feedback will help learners see the next steps to take in order to move closer to the learning goal. It might seem like there is a tension between asking good questions and offering concrete steps for improvement. Let’s consider a few examples to explore that tension:

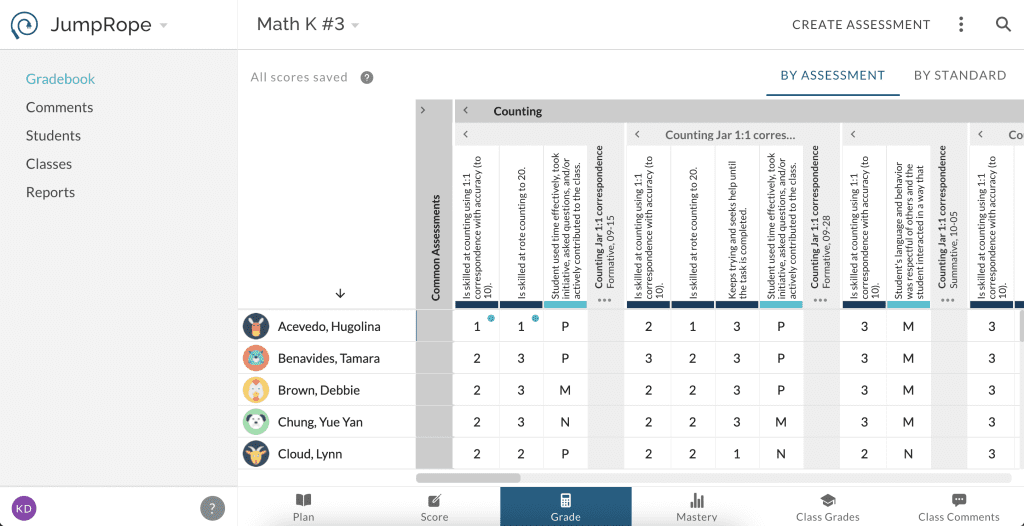

In JumpRope, teachers can offer specific feedback for any learning goal and have it visible to students and parents on the portal.

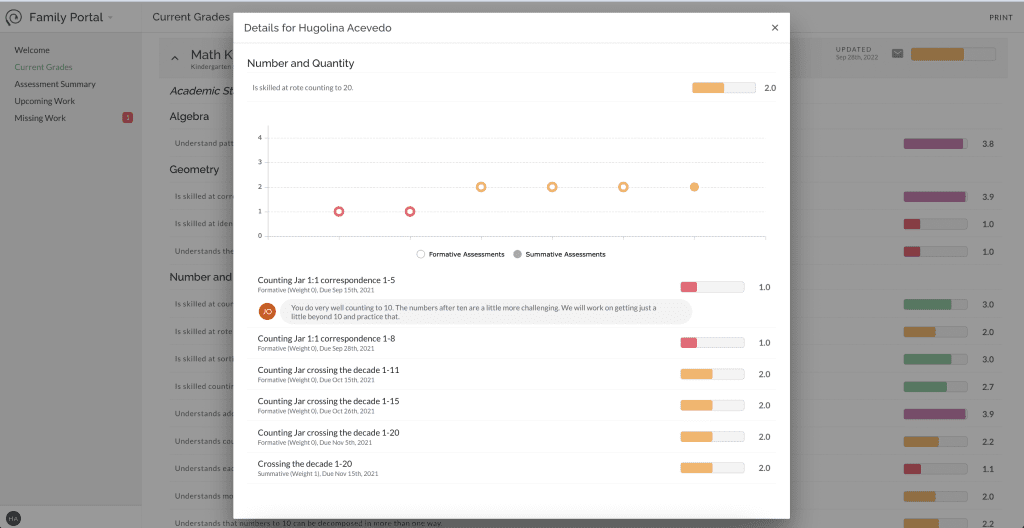

This is how students and parents see feedback in JumpRope’s family portal

In JumpRope teachers can double click a score to provide feedback

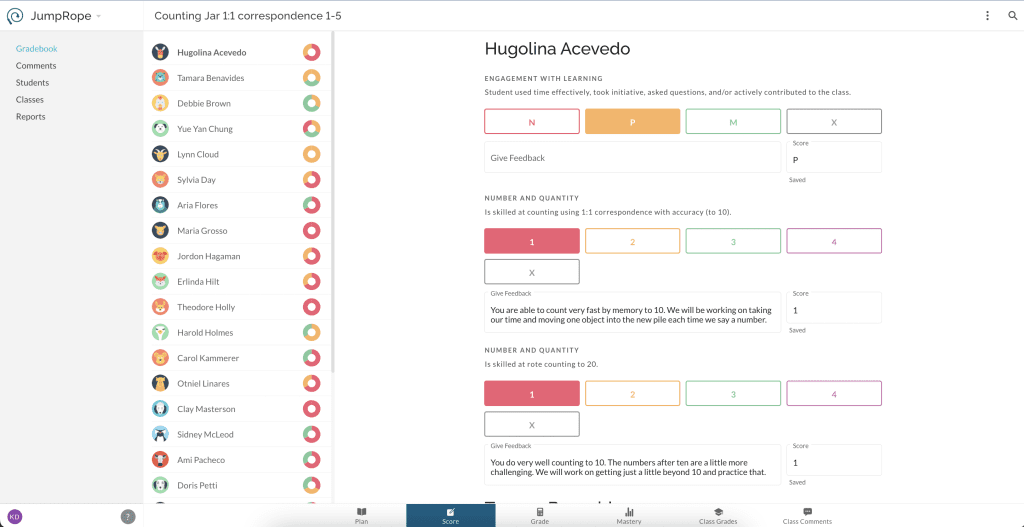

Teachers can provide feedback though the score view in the JumpRope app

When the feedback is offered with plenty of time available to students to act on it, and also explicitly dedicated to that cause, we ensure that our careful guidance, our energy toward individualizing the learning comes to fruition. We need to build into the learning arc classroom-based time for students to examine our feedback and put it to good use.

The more mindfully I plan for the feedback I offer my students, the more they take from it. That mindful planning starts with the deliberate steps I take to get to know them as learners and as people — building trust. It includes thinking explicitly about when during their learning process they most need to hear from me, how I will share my questions and prompts, and what I expect them to do with the feedback. I’m always careful to let them know where their strengths are, but I know that one of the most effective ways to get each of them to grow is to help them see where and how to grow.