Editors note: This post provides a deeper look into the ideas of Equity of Opportunity, one of JumpRope’s Core Values.

The bedrock of effective instruction and assessment is the knowledge we have of our content, pedagogy, and our students. The three-way overlap formed by those intersecting spheres is the sweet spot we should all be seeking. Back in September, I wrote about matching instructional strategies to learning goals. In that post, I made the case for considering the learning targets as the drivers for choosing instructional methods. The caveat I’d like to add now, the other driver for choosing best fit instructional strategies, is knowing our students. Of course, there are many layers for a teacher in getting to know her students. Who are they as people? What captures and holds their interest? What are their lives outside of school like? How do they perceive themselves? Way back in 2013, I offered these brief musings on the value of knowing our students as people. As part of the exploration of our core values we’re engaging in through this year’s blog posts, I’d like to take some time elaborating on the merits of planning for the specific learners in our classroom and planning for the specific ways people learn.

We need to think about how a student who has Dyslexia, ADHD, or a processing challenge (three common disabilities found in schools) will reach their learning targets. Which resources, instructional strategies, and supports should we put in place to help those students succeed?

When I think about deliberate planning for learners, I consider a range of lenses through which to look. Those lenses include IEPs and 504 plans, as well as RTI plans. We need to think about how a student who has Dyslexia, ADHD, or a processing challenge (three common disabilities found in schools) will reach their learning targets. Which resources, instructional strategies, and supports should we put in place to help those students succeed? JumpRope has partnered with Education Modified to allow teachers instant access to both information, like student classifications under IDEA or DSM-5 diagnosis, so teachers know which of these common disabilities a student has, but also recommends research-based instructional strategies. Looking through a wider lens, we will see students who are not identified in some way but who might still benefit from a specifically considered approach to the content.

And of course, any study of learners and learning reminds us that we all move toward targets and goals in our own unique ways. So, while the planning process must include knowledge of specific students’ plans–after all, they are legally binding documents–systems like Education Modified can house documentation and provide workflow tools to access, update and share IEP or 504 documentation, as well as behavior plans, ELL plans and transition plans.

Once we acknowledge that learning happens in different ways for all people, it makes sense to then plan with a research-based frame like Universal Design for Learning or differentiated instruction. From a planning perspective, differentiated instruction asks us to begin with an understanding of learning or an understanding of learners respectively. Gaining traction in schools in the mid- 1990’s, differentiated instruction, popularized by Carol Ann Tomlinson, asks us to consider the learners in our classroom. As we plan, we differentiate content, process, product, and environment according to things we know about our students’ readiness, interests, and learning profiles. We begin, therefore, with who the students in our classroom are: their abilities, background knowledge, likes and dislikes, and everything else we can marshal about them to know them as learners. Differentiation was and continues to be an excellent model to help us shift the focus of our pedagogy toward the people who are learning. It provides a sound response to teacher-centered instruction. It helps us ask “how will the students learn this content, these skills,” as opposed to “how will I teach this content, these skills?” If the ballast of the question rests with student learning, the answer will necessarily include direction for our instruction, but if the ballast rests with our instruction, we run the risk of the students missing the mark with the learning.

Seen through a UDL lens, learning is inherently variable; it encourages us to think about a range in abilities as opposed to abilities and disabilities.

Popularized several decades after differentiated instruction, the UDL approach considers the entire notion of learning as opposed to considering specific learners or groups of learners. Seen through a UDL lens, learning is inherently variable; it encourages us to think about a range in abilities as opposed to abilities and disabilities. Like differentiation, UDL asks teachers to offer multiple representations of content so learners can access it through reading, listening, and viewing, for example. It asks teachers to offer those same types of options to students as they demonstrate their learning. And, as Amanda Morin of Understood tells us, it asks teachers to give students choices and create flexible environments that open several doors to learning at any one time. In writing about UDL in the classroom, Allison Posey, also of Understood, reminds us of the connection between UDL and some of the foundational tenets of proficiency-based learning: knowing the goal, student ownership, and providing a range of pathways and resources. Of course, if we are keyed into who our specific learners are, we can make better choices as we plan, but as UDL indicates, embracing the idea that learning will happen in myriad ways should compel us to plan for that learning with as much flexibility as possible because we know that wide range of learners will be in our classroom.

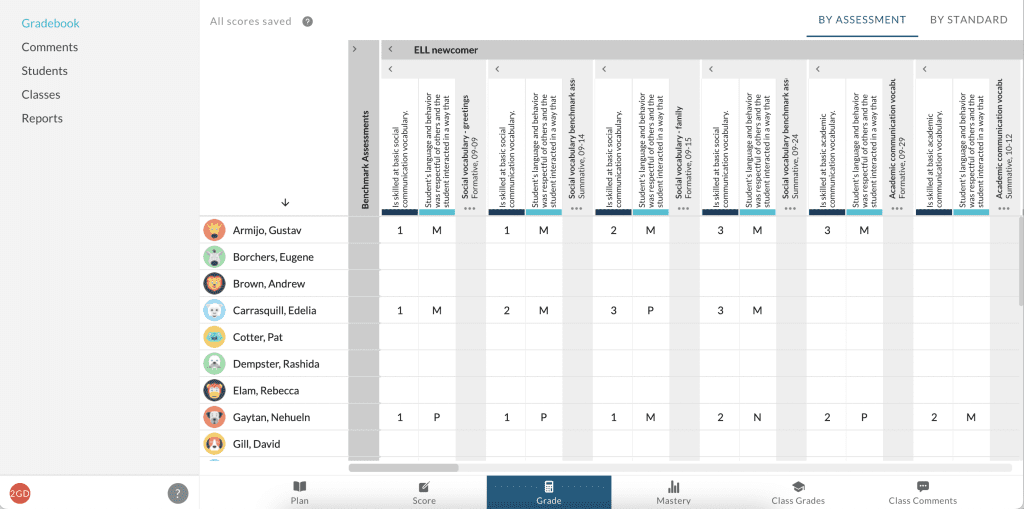

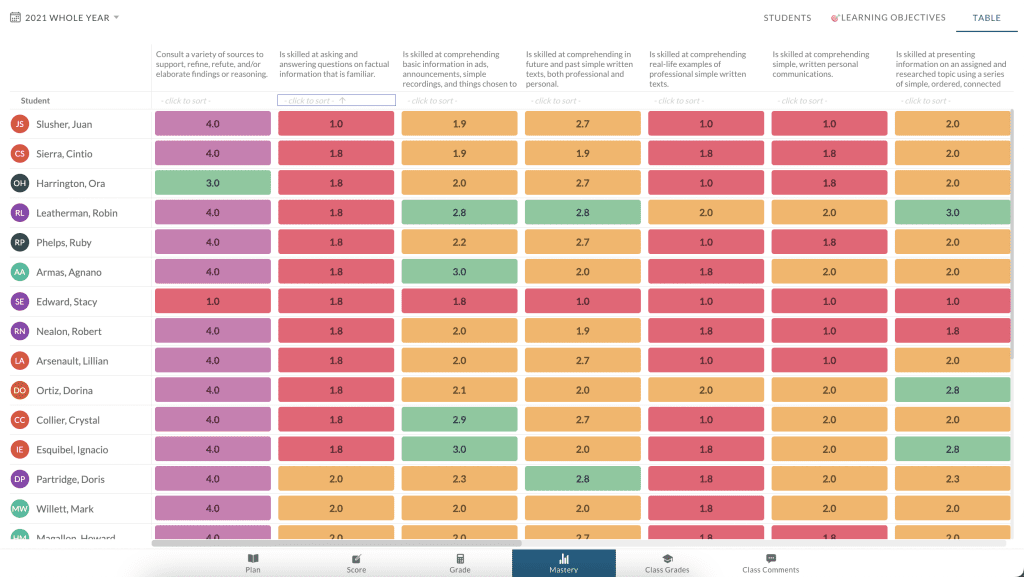

When teachers use UDL to assess students in different ways, they can easily track and manage that assessment data in JR. Like in example1 below, within the plan tab, putting 3 different types of assessments, linked to the same standards, allows us the flexibility to offer different ways for students to show learning on the same standards. JumpRope also supports teachers who differentiate instruction and assessment according to individual student needs. Using the table view of mastery to view students’ progress on specific indicators, as shown below in example 2, gives us a way to consider who needs additional time and support, and to group students for specific instructional strategies. In looking at the table below the indicator “Subtract within 20” helps us see a group of four students not yet meeting expectations. These four students could be grouped to receive additional instruction while students not yet meeting a different target would constitute another group to receive additional support.

UDL Example 1

Tomlinson Example 2

As we begin to plan lessons and units of instruction, we know that what needs to be learned is an important, but incomplete, frame to use. That frame is completed by deepening our understanding of learning itself and how the learners in our classroom will engage with that process. When we can clearly define and articulate learning goals, and flexibly support the process of learning because we embrace principles like those espoused through UDL and/or differentiated instruction, we set our students on the path to success.