Emily Rinkema and Stan Williams are Humanities teachers at Champlain Valley Union High School in Hinesburg, VT.

Since moving to standards-based learning (SBL) in our classroom last year, the biggest difference has been the shift in focus from teaching to learning. For the first 15 years of our teaching careers, we planned by thinking about what we were going to teach. We came up with clever and engaging ways to teach grammar, to teach the Mongols, to teach Lord of the Flies. We taught about Medieval literature, the structure of the sonnet, and why the Renaissance followed the Middle Ages. We moved through the content from topic to topic and hoped everyone was following along. Students did (or didn’t do) their homework, earned points (or didn’t) for participation and quizzes, and prepared (or didn’t) for their final assessments. We knew we were successful when students liked class and got good grades on the tests or the essays or the projects, which led to good grades in the class (which did or didn’t reflect what they actually knew and understood). When teachers in the upper grades asked what we had covered, we could confidently provide a list of topics and content. But no one ever asked what our students had learned.

What we teach and what students learn are potentially completely different, and it wasn’t until we realized that the first is virtually irrelevant that we began to make significant changes in our instruction.

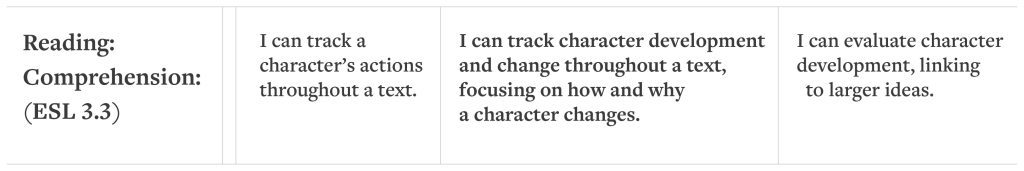

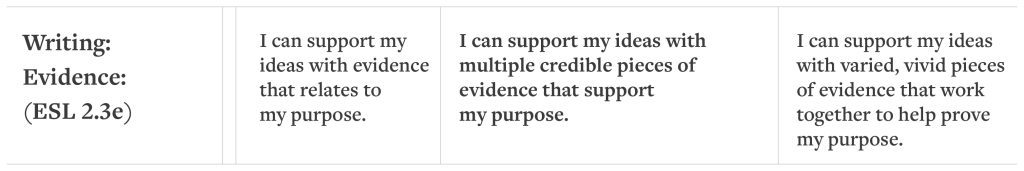

The key to these changes was our move to SBL and, more specifically, our use of transferable skill learning targets and scales. Learning targets are student friendly standards meant to guide instruction and feedback, and scales are the skill continuums in which the targets exist. The language is specific, precise, and invitational, not evaluative – in other words, it shows students what a skill looks like without an overt judgment of quality. Here are two examples of unit learning targets with scales (the continuum moves from left to right). The bold, center column is the actual target for the unit:

As soon as we created targets about learning, our focus became learning, and one of the first changes we had to make was to our gradebook; it no longer made sense to keep track of assignments and points (i.e. Romeo and Juliet Quiz: 8/10, Medieval Coat of Arms Reading: 12/20), because those grades told us nothing about learning (in fact, these grades were often more about compliance than anything else). So we switched to JumpRope, a gradebook that allowed us to keep track of what our students were actually learning, not just what we assigned or taught. We now set up our gradebook by target, so at any point in the unit we can see who has already met our targets, who needs more practice, and who needs more instruction. Our gradebook is no longer a static place to record grades, but instead helps us track, plan, and analyze. It helps us communicate learning.

Since we moved to SBL, learning has become transparent – for us and for our students. With transparency of learning comes incredible responsibility (and sometimes guilt). It is our job to ensure that our students learn. It is not our job to ensure that we teach (we wouldn’t need students to do that). When we look at the gradebook and see that we have a group of students who cannot yet meet the target, we must respond to that knowledge. In the past, we might have said, “We don’t have time to slow down because we have to get to the Mongols by Friday,” and though we would have felt bad, we would have moved on. But when our priority is learning, we need to find a way to return to the targets, even if it’s inconvenient. This is not easy. It requires a shift in how we look at class design and instruction; it requires differentiation to ensure that those who are ready can move on to more complex skills or different targets; it requires patience and creativity.

The shift from teaching to learning in our classroom means that our content no longer drives what we do. We no longer teach the Mongols; we use the Mongols to help students learn to read critically, to find evidence to support a thesis, or to practice inductive reasoning. And by making this switch, our students not only improve their transferable skills, but learn (and remember!) more about the Mongols than they ever did in the past.

At the end of the day, the unit, the year, what matters is what our students have learned. And this realization has changed teaching for us forever.